A personal study of an artist as a young man who was lost too soon

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s short life is explored by friend Roger Guenveur Smith in a moving Penumbra performance. The post A personal study of an artist as a young man who was lost too soon appeared first on MinnPost.

Roger Guenveur Smith has been exploring the art form of solo performance for decades, bringing to life historic characters like Huey P. Newton, Frederick Douglas, and Rodney King. He’s also worked in films, including numerous collaborations with Spike Lee, who has adapted two of his one-man-plays for the screen.

“In Honor of Jean-Michel Basquiat” differs somewhat from his other solo plays because Smith draws on his own memories of becoming friends with Jean-Michel Basquiat, rather than solely relying on historical research. It’s a portrait study of an artist as a young man whose life and career were cut short by tragedy.

Smith centers his story of Basquiat in Los Angeles, where he met the artist in the fall of 1982. The play paints a picture of a thumping party scene happening on the West Coast at the time, and uses the piece to unpack what made Basquiat tick as an artist.

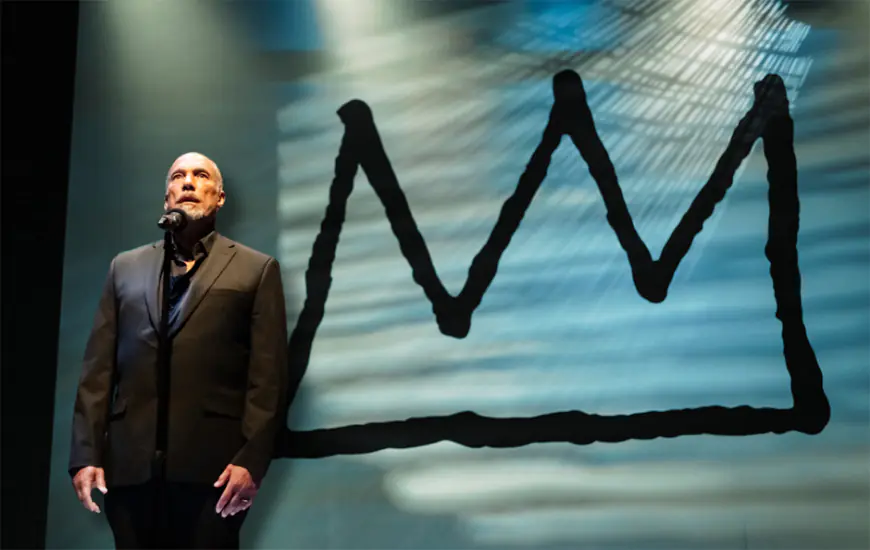

Throughout the performance, a giant image of a crown hovers behind him. The crown never moves, but the lighting by designer Wu Chan Khoo, at times washed in scaffolded shadows, shifts in tone and color.

Painted by local artist Seitu Jones, the crown replicates one of Basquiat’s signature motifs from his early days as a street artist. It’s a minimalist crown— with just three points at the top, and a thick outline. Basquiat used the symbol often— whether as a central image, something that would punctuate a figure, or as part of his use of text and symbols.

There are people whose light shines too bright to remain on this earth for too long. Basquiat died at the age of 27, from a drug overdose, robbing the world of all the art he could have made if he had stayed here a little longer.

While he didn’t die quite as young, I’m reminded of Prince, whose given name (after his father’s stage name) nods to royalty like Basquiat’s crowns. He died at 57, also of an overdose. Just think if they had stayed alive just a bit longer— what they could have created.

In Smith’s performance, the image of the crown acts as proxy for Basquiat himself, and it also elevates the artist as a royal or even God-like figure. As humble of a design as it is, the crown marks Basquiat in a lineage of Black brilliance. From musicians like Charlie Parker and Billy Holiday to athletes like Cassius Clay (later Mohamed Ali) and Edwin Moses, Smith reflects on Basquiat’s place amongst those greats.

He ponders his own relationship to that lineage as well. Smith begins the show by recreating a conversation with his father, who acts disapprovingly of the actor’s chosen career. Later, he marvels at Basquiat’s ability to channel the first impulses of a child’s wild imagination. Smith seems to be awed by his friend, and perhaps have some longing for that level of artistic revelation.

He also layers his own trajectory as an artist into the narrative— specifically his role as Smiley in Lee’s “Do the Right Thing.” In the film, Smith plays an artist with a developmental disability. He draws pictures of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. and tries to sell them to people, similar to how Basquiat in his early career would make postcards and sell them around SoHo, and once sold a postcard to Andy Warhol.

In the movie, after Radio Raheem is killed by police, Smiley shouts, “One of the police was Black!” and lights a match that burns down the pizzeria. Again, there’s a connection here to Basquiat, who in 1981, created a painting called “Irony of Negro Policemen.”

The satirical work employs a grotesque, childlike style to question why people from the Black community would participate in an institution prone to violence against them.

As an artist, Basquiat often took this kind of subversive approach in work that questioned power, capitalism, white supremacy, and hypocrisy. Coincidentally, another film by Spike Lee that Smith acted in—“Get on the Bus,” came out the same weekend in 1996 as a biopic about Basquiat, directed by visual artist Julian Schnabel. It had mixed reviews— Roger Ebert praised Jeffrey Wright’s performance as the title role and David Bowie’s performances as Andy Warhol, but others accused the film of whitewashing Basquiat’s story.

There’s a scene in the movie where we watch Basquiat painting a large canvas on the floor of his studio apartment (the painting isn’t a replica, as Schnabel couldn’t get the rights from the family, so it’s Schnabel’s own painting in the style of Basquiat). There’s no dialogue in the scene— instead, we watch Wright paint while he listens to Jazz. The scene shows how deeply connected Basquiat was to music.

Smith makes this point too, and talks about how Basquiat idolized Charlie Parker. He also structures his piece musically. Accompanied by a score by sound designer Mark Anthony Thompson, he riffs through stories, going from one thought to another by association. I did sometimes struggle to keep up with the different lines of thought as Smith moved through scenes and images, references to pop culture and historical events. And yet I appreciated how the performance took on the style of an abstract expressionist painting, or a piece of jazz music. It wasn’t always linear—- instead it followed an intuitive path.

It was quite moving as well. Smith is a captivating performer, wholly engaged in the moment, whether he’s engaged in intense curiosity about the nature of artmaking, or sharing his experiences of connecting to a stranger in a moment of grief.

It’s playing one more weekend.

Wednesday, Oct. 23-Friday, Oct. 25 at 7:30 p.m., Saturday, Oct. 26, at 2 p.m. and 7:30 p.m., Sunday, Oct. 27, at 4 p.m. at Penumbra ($45). More information here.

Sheila Regan

Sheila Regan is a Twin Cities-based arts journalist. She writes MinnPost’s twice-weekly Artscape column. She can be reached at sregan@minnpost.com.

The post A personal study of an artist as a young man who was lost too soon appeared first on MinnPost.

What's Your Reaction?