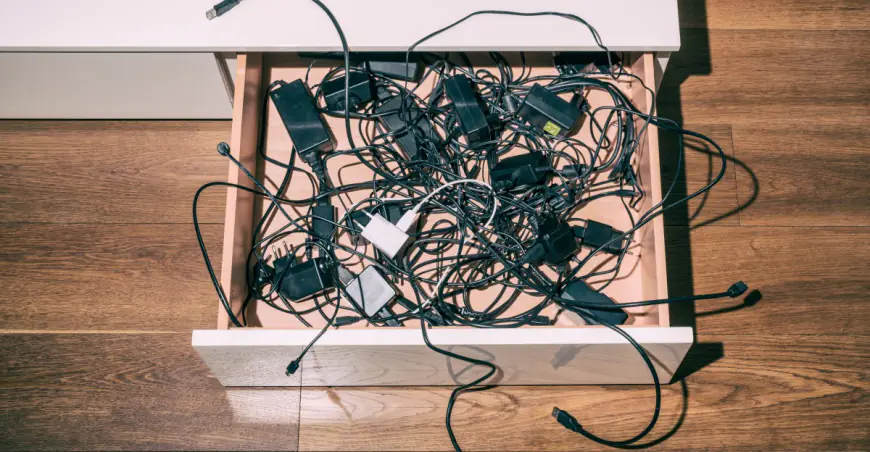

Your drawer full of old cables is worth more than you think

In an old cabinet, stashed away at the back of my closet, there are not one, not two, but three drawers full of old cables and devices. Every generation of USB is represented as is every major brand of gadget. I know that I won’t use these cables again, but I also know they don’t […]

In an old cabinet, stashed away at the back of my closet, there are not one, not two, but three drawers full of old cables and devices. Every generation of USB is represented as is every major brand of gadget. I know that I won’t use these cables again, but I also know they don’t belong in the trash. I have no excuse for not recycling them.

I’m not the only one. Globally, a paltry 12 percent of small electronics get recycled, according to a 2024 UN report. The numbers don’t get much better for larger electronics. That means billions of pounds of equipment, from old iPods to broken TVs, gets thrown away. Those discarded electronics, commonly known as e-waste, are filled with valuable metals that end up in landfills along with dangerous chemicals that can leach into the soil and groundwater. Beyond that, there’s a veritable treasure trove of critical materials that gets lost when these devices aren’t recycled.

“One of the things that I think that consumers don’t know, and they should, is that it’s way easier to recycle electronics than you might think,” said Callie Babbitt, a professor in the Rochester Institute of Technology’s sustainability department.

“By recycling a product, you’re able to offset the energy and the materials that it would take to manufacture a new one,” Babbitt added. “And that means we don’t have to mine as many materials from sometimes vulnerable and ecologically sensitive parts of the world.”

Recycling e-waste is not as straightforward as recycling aluminum cans. It’s not exactly rocket science, either.

Many big-box stores will recycle your old electronics for you, as will a growing list of recycling centers. But that fact won’t solve the global e-waste crisis. Humans created 137 billion pounds of e-waste in 2022, which makes e-waste one of the fastest growing solid waste streams in the world. Finding a place to put all that trash isn’t the only problem. It’s extremely energy intensive to mine for the critical metals needed to manufacture electronics, so reusing those components is essential in the fight against climate change. And we can all do our part to help address it.

It might sound like an exaggeration to say that Americans have billions of dollars worth of world-saving materials in their junk drawers. But it’s not. It’s actually more like $60 billion worth of stuff.

Now that the holiday season is fully upon us, consider giving those materials back to the world. If you just bought a new phone, for instance, don’t throw the old one in the trash. Definitely don’t put it in that drawer in the back of your closet. Someone will probably pay good money to take it off your hands.

The surprisingly complex e-waste crisis

The term e-waste might make you think of boxes full of old circuit boards, and that’s partially correct. Old circuit boards, cables, and screens all contain small amounts of valuable elements like copper, gold, and silver that can be extracted and reused. However, as microchips have found their way into more and more products, the definition of e-waste has expanded to include everything from light-up kids’ toys to toasters.

The world’s e-waste problem is getting bigger, in part because we’re just making and consuming more electronics, including products that can’t be repaired or were designed to have short lifecycles. (Looking at you, Apple AirPods.) That 137 million pounds of e-waste created by humans in 2022 breaks down to 17 pounds of e-waste per person. Only about 22 percent of it was formally collected and recycled. Compare that to the more than 50 percent of aluminum cans that get recycled and it’s easy to see we have some work to do.

Ramping up e-waste recycling would make us less reliant on the destructive and energy-intensive mining operations around the world. In addition to their significant greenhouse gas emissions, mining for the types of metals we need to build electronics also damages local ecosystems and hurts biodiversity.

Many of the critical minerals needed for things like smartphones and clean energy tech, including solar panels and EVs, also come from countries with records of abusive working conditions in mines. Those metals, which include indium (used in touchscreens), tantalum (for capacitors that store energy), and germanium (for semiconductors like microchips), typically aren’t found in the US, so recycled electronics are a key way to build up a domestic supply chain for these elements.

“There is a global effort right now — almost a race, if you want to say it that way — for countries to have access to rare earth elements,” said Nena Shaw, director of the Resource Conservation and Sustainability Division at the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). “And so the US wants to keep what we have.”

We’ll need a lot more of those critical materials in the years to come, too. Demand for cobalt, which is essential for EV batteries, will grow fivefold by 2050, according to the International Energy Association. Demand for lithium, also a key battery ingredient, could grow tenfold by 2050.

You probably have some lithium in a drawer somewhere, maybe inside an old phone’s battery. Throwing that phone in the trash is a bad idea, if only because lithium-ion batteries have an unfortunate tendency to catch on fire and then set entire landfills on fire. Recycling is a better idea but only if done right.

The scramble to recapture an estimated $62 billion worth of unclaimed materials has created an informal e-waste recycling market with harmful consequences. That includes the rise of urban mining, where electronics are recycled and refined on the streets of low-income countries. This leads to toxic fumes harming local workers and residents and corrosive chemicals being dumped in rivers. The UN estimates that about half the world’s recycled e-waste goes through informal channels.

So how can you make sure that phone ends up in the right place? The short answer is to go through a big-box retailer, like Best Buy. The longer answer is to seek out certified e-waste recyclers in your area, which requires a tiny bit of knowledge about how the industry works.

How to recycle anything with a power switch

The world of formal e-waste collection and recycling is booming. After all, the stuff being recycled is literally full of gold and other very valuable minerals. E-waste recyclers face two big challenges, however. One, recycling old electronics is notoriously complex. Two, not enough people recycle old electronics.

Let’s start with the complex bit. In order to get at the reusable parts of an old phone or TV, recyclers have to tear the thing down to its most basic components. That means ripping off the plastic shell, tearing out the circuit board, and so forth. Recovering the valuable material from those components is more difficult, as it usually involves either melting down the components or bathing them in acid.

This process could work better, and plenty of people are trying to figure out how. One of them is Terence Musho, an associate professor of engineering at the West Virginia University. Musho led a DARPA-funded project to develop a modular e-waste recycling system.

“The holy grail of e-waste recycling is if you could shred your whole iPhone, run it through some process, and get out select metals,” Musho told me. “We’re not quite there yet.”

One thing that would help: More people need to recycle e-waste. Figuring out exactly where to go can be a challenge.

All you really need to know is how to find certified e-waste recyclers. Just look for one of these two main certification programs out there: R2 and e-Stewards. (Click through those links to find recyclers near you.) Certified R2 and e-Steward recyclers will know how to handle your e-waste in a safe, environmentally friendly way, and they’ll also be mindful of your data security, since you don’t want a scavenger discovering an old hard drive with your banking info on it.

You don’t have to hunt down an e-waste specialist to recycle your old gadgets, though. You can actually drop off most old electronics at big-box stores, including Best Buy and Staples. You can take batteries, fluorescent light bulbs, and plastic bags to Home Depot. Everything else can go to certain Goodwill locations that have a partnership with Dell to recycle e-waste. If you’re still at a loss for drop-off sites, Earth911 and Call2Recycle have handy hyperlocal guides.

There are also plenty of ways to get rid of your old electronics and get something back. Big-box retailers, including Best Buy and Amazon, have trade-in programs for certain devices, as does the popular refurbished electronics marketplace Back Market. There are also smaller sites like Decluttr and Swappa that accept old gadgets and give you credit on refurbished ones, kind of like a used book store would for your old books.

If all else fails, there’s bound to be an e-waste recycling event in your town or county at some point in time. The New York City Department of Sanitation, for instance, had one at my local library last month.

I regret missing it. After all, those drawers full of cords and old gadgets aren’t going to recycle themselves.

A version of this story was also published in the Vox Technology newsletter. Sign up here so you don’t miss the next one!

What's Your Reaction?