Diabetes 'a huge public health problem'

You know what's a great motivator for dieting? The prospect of going blind. Or having your fingers become permanently numb. Focuses the mind wonderfully.Or maybe that's just me. I immediately snapped to the idea that diabetes (which I wrote about contracting on Monday) means your body isn't processing insulin properly, causing sugar to overload your bloodstream and rot your plumbing. I leapt to get my blood tested, see a doctor, do whatever I'm told: take drugs, banish sugar and carbohydrates from my diet.But maybe that's just me. Maybe I'm an exception. How many diabetes patients receive their diagnosis and then do what they're supposed to do? Opinion bug Opinion "The minority," said Dr. Anthony J. Pick, an endocrinologist at Northwestern Medicine. "There's a lot of inertia. People who go years with poorly-controlled diabetes. Because it's a chronic disease, and it's a lifestyle. A lot of patients struggle."With nearly half the country overweight, diabetes has skyrocketed — a third of American adults are prediabetic; 10% have the disease."It's probably getting worse," Dr. Pick said. "It's fairly depressing when you look at the level of diabetes care. It's a huge public health problem."Especially given the silly stuff we do obsess over — shark attacks, asteroid strikes — diabetes doesn't get the attention it deserves."There's a lack of awareness," agreed Dr. Pick. "Diabetes is the tip of the spear of chronic poor lifestyle disease: fatty liver, sleep apnea. The number one killer is cardiovascular disease, and diabetes feeds right into that." Dr Anthony J. Pick is an endocrinologist at Northwestern Medicine. Endocrinologists are in severe short supply, forcing general practitioners to monitor treatment, aided by diabetes educators. New patients can expect to wait a year to get an appointment to see Dr. Pick.Photo provided by Northwestern Medicine Diabetes runs in certain populations: Blacks, Latinos, Asian-Americans get more than their share."Pima Indians have a 90% incidence of diabetes," said Dr. Pick. "In certain populations, the numbers are staggering."The jury is still out, but it seems that I didn't get mine from poor lifestyle habits — being obese, not exercising, smoking, etc. (Type 2) — but from my body attacking my pancreas (Type 1). A genetic alarm clock went off, perhaps nudged by other factors medicine hasn't yet pinpointed. Dr. Pick said perhaps even COVID might play a role.For every guy like me who views the diagnosis as a firebell in the night, many others treat it as just another vague peril to be shrugged off."I see neglect," said Dr. Pick. "Day after day, lack of respect and appreciation of how dangerous diabetes is over time."In a weird way I'm lucky, because my diabetes presented itself with clear, hard-to-ignore symptom: scouring thirst being No. 1. My doctor's first approach — take Metformin and see me in a month — did not fix the problem.I might have been more patient letting Metformin work, but my fingers were also tingling — diabetes causes neuropathy — and I need them to type. After a week, I was back with a screech of, "This isn't working!"OK, he said, and put me on a continuous blood monitor — a Dexcom G7 — a heretofore unimagined high-tech gizmo. You take an applicator as big as the top of a shaving cream can, press it to the back of your arm, and it attaches a monitor the size of a quarter. The monitor talks to your cell phone, and gives you another app to check. Gmail. Instagram. Blood sugar.The Dex amped up anxiety without offering a solution. One night I had a bowl of Shredded Wheat and blueberries for dinner — thinking, "low sugar!" — and my blood peaked at 400. Sometimes a patient needs to listen, sometimes to advocate for himself. I went running back to the doctor and practically begged him to put me on insulin.The thing with insulin is you can't take it as a pill. You have to inject it. This seems off-putting, but is surprisingly simple. They give you a pen that holds about 15 doses. You screw on a disposable needle, grab a handful of fat at your waist, jam it in, push the button, and you're good to go. It doesn't hurt.There's more. We'll wrap this up Friday spotlighting the many readers — thank you all — who wrote in with advice and observations, a community of concern whose voices deserve to be heard.I don't want to drive off what non-diabetic readers are still here — I know nobody wants to hear an ill person prattle on endlessly about his sickness. But given that diabetes affects tens of millions of American, that we don't have a

You know what's a great motivator for dieting? The prospect of going blind. Or having your fingers become permanently numb. Focuses the mind wonderfully.

Or maybe that's just me. I immediately snapped to the idea that diabetes (which I wrote about contracting on Monday) means your body isn't processing insulin properly, causing sugar to overload your bloodstream and rot your plumbing. I leapt to get my blood tested, see a doctor, do whatever I'm told: take drugs, banish sugar and carbohydrates from my diet.

But maybe that's just me. Maybe I'm an exception. How many diabetes patients receive their diagnosis and then do what they're supposed to do?

"The minority," said Dr. Anthony J. Pick, an endocrinologist at Northwestern Medicine. "There's a lot of inertia. People who go years with poorly-controlled diabetes. Because it's a chronic disease, and it's a lifestyle. A lot of patients struggle."

With nearly half the country overweight, diabetes has skyrocketed — a third of American adults are prediabetic; 10% have the disease.

"It's probably getting worse," Dr. Pick said. "It's fairly depressing when you look at the level of diabetes care. It's a huge public health problem."

Especially given the silly stuff we do obsess over — shark attacks, asteroid strikes — diabetes doesn't get the attention it deserves.

"There's a lack of awareness," agreed Dr. Pick. "Diabetes is the tip of the spear of chronic poor lifestyle disease: fatty liver, sleep apnea. The number one killer is cardiovascular disease, and diabetes feeds right into that."

Dr Anthony J. Pick is an endocrinologist at Northwestern Medicine. Endocrinologists are in severe short supply, forcing general practitioners to monitor treatment, aided by diabetes educators. New patients can expect to wait a year to get an appointment to see Dr. Pick.

Photo provided by Northwestern Medicine

Diabetes runs in certain populations: Blacks, Latinos, Asian-Americans get more than their share.

"Pima Indians have a 90% incidence of diabetes," said Dr. Pick. "In certain populations, the numbers are staggering."

The jury is still out, but it seems that I didn't get mine from poor lifestyle habits — being obese, not exercising, smoking, etc. (Type 2) — but from my body attacking my pancreas (Type 1). A genetic alarm clock went off, perhaps nudged by other factors medicine hasn't yet pinpointed. Dr. Pick said perhaps even COVID might play a role.

For every guy like me who views the diagnosis as a firebell in the night, many others treat it as just another vague peril to be shrugged off.

"I see neglect," said Dr. Pick. "Day after day, lack of respect and appreciation of how dangerous diabetes is over time."

In a weird way I'm lucky, because my diabetes presented itself with clear, hard-to-ignore symptom: scouring thirst being No. 1. My doctor's first approach — take Metformin and see me in a month — did not fix the problem.

I might have been more patient letting Metformin work, but my fingers were also tingling — diabetes causes neuropathy — and I need them to type. After a week, I was back with a screech of, "This isn't working!"

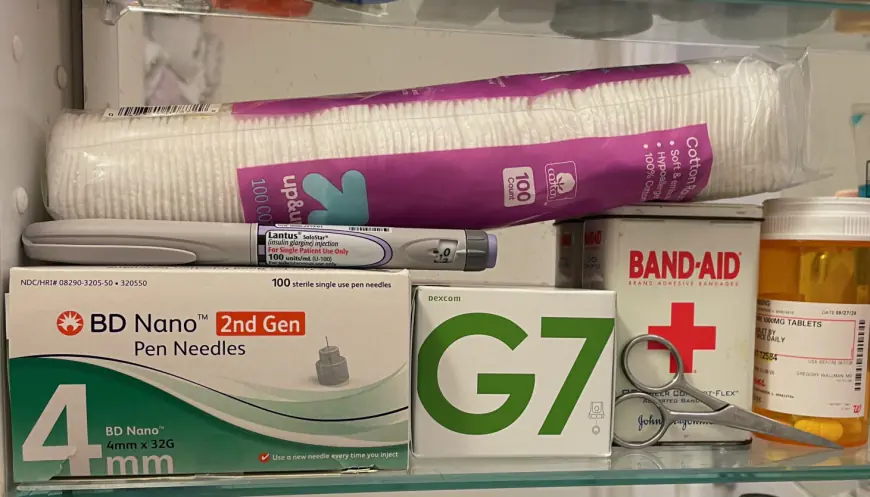

OK, he said, and put me on a continuous blood monitor — a Dexcom G7 — a heretofore unimagined high-tech gizmo. You take an applicator as big as the top of a shaving cream can, press it to the back of your arm, and it attaches a monitor the size of a quarter. The monitor talks to your cell phone, and gives you another app to check. Gmail. Instagram. Blood sugar.

The Dex amped up anxiety without offering a solution. One night I had a bowl of Shredded Wheat and blueberries for dinner — thinking, "low sugar!" — and my blood peaked at 400. Sometimes a patient needs to listen, sometimes to advocate for himself. I went running back to the doctor and practically begged him to put me on insulin.

The thing with insulin is you can't take it as a pill. You have to inject it. This seems off-putting, but is surprisingly simple. They give you a pen that holds about 15 doses. You screw on a disposable needle, grab a handful of fat at your waist, jam it in, push the button, and you're good to go. It doesn't hurt.

There's more. We'll wrap this up Friday spotlighting the many readers — thank you all — who wrote in with advice and observations, a community of concern whose voices deserve to be heard.

I don't want to drive off what non-diabetic readers are still here — I know nobody wants to hear an ill person prattle on endlessly about his sickness. But given that diabetes affects tens of millions of American, that we don't have a full-time medical writer covering this stuff, and since I managed to write a three-part series on picking up after dogs in 2021, I'm going to risk revisiting this topic again on Friday.

What's Your Reaction?